THE PILGRIM PEOPLE OF GOD

In this article Professor Gavin D'Costa examines the metaphor of the 'pilgrim people of God'

and explains its relevance to the Church today

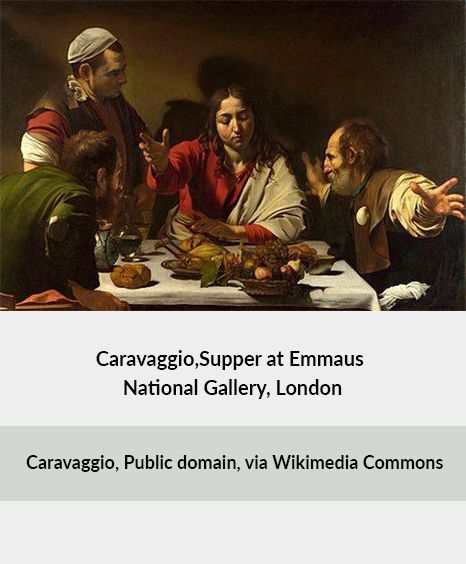

The church is founded after the resurrection through a pilgrimage story – but one where the travellers were sad and confused and not quite sure where they were going as human beings. That is probably the case with many of us. The disciples were walking to Emmaus - and were disoriented by the events that had led to Jesus’s violent death on the cross. Their hopes and community spirit were shattered. Their Lord and Master was murdered. This is the story found in Luke (24: 13ff). It takes a fellow walker, the risen Christ – who they do not recognise, to change things – to help them see things freshly. But looking with new eyes only happened through taking time, taking a long walk, talking and listening, and eating together at the end of that walk. Jesus explains to them what happened in his life and ministry through recalling the scriptures. And the penny only drops for the disciples when they stop to eat and drink with him, slowly processing everything he’d said. When they see him and recognise him, he is gone. And he is always with them in their eating together.

And then they are thrilled and rush to tell the others. The Church is formed. And almost immediately the disciples are again on pilgrimage, wanting to share with others – travelling slowly, learning, preaching, sometimes shaking the dust off their sandals, eating together and praising God, quarrelling and falling out. They are in the process of becoming a community that welcomes those who are feeling unsettled and disoriented and find in the story of Jesus: good news; new life; new community – and the difficulties of keeping community together.

This ‘pilgrim church’ image is picked up at the Second Vatican Council. It nicely balances a number of images of the Church which should be kept in healthy tension, not resolved, for their full effect to dazzle and illuminate. Images work like this, like poetic language. Take either the first or second image away in this beautiful Shakespeare line and the whole collapses: ‘O, that this too too solid flesh would melt Thaw and resolve itself into a dew! Or that the Everlasting had not fix'd His canon 'gainst self-slaughter!’.

The Church had been called the ‘mystical body of Christ’ by Pius XII in his encyclical of that name (1943). Pius wanted to underline that Jesus Christ founded this community, was present in its sacraments and hierarchy, and if you want to see Christ, you should look at the visible elements of the Church that are holy: the sacraments as generators of grace and blessings; the scripture that testifies; and those to whom these are entrusted, the bishops united under the Pope, as a visible sign of their unity – with all the people of God. This image of the mystical body was grounded in St Paul. Some were concerned that this conveyed a triumphalism in identifying the Roman Catholic Church with this mystical body, while this teaching also spoke a profound and important truth.

The Second Vatican Council (1963-65) kept this important image of the ‘mystical body’, while also bringing into play the ‘people of God’ and the ‘pilgrim church’ in its document ‘Lumen Gentium’, the ‘Light to the Gentiles’ – a name given to the Church regarding its mission and meaning. Click on the button below for the full document

The Church was not a community meant to exist for itself, but to be a light to the nations: reflecting the love and mercy of God. People of God and pilgrim church bring out two important themes.

First, the journey to holiness is one undertaken by each and everyone who is baptised, not just those in religious orders or bishops and priests. It is a journey for the entire people of God.

This was always of course true but was a theme that required renewed attention. This often happens in the history of the Church – one element gets stressed for particular reasons and other elements are thereby neglected. Chapter 5 of ‘Lumen Gentium’ was called ‘The Universal Call to Holiness’. It portrays the many means by which each and every person can grow in holiness, a journey that is never finished until death. Right from the start, going on pilgrimage with others who sought living waters and refreshment that allows us to return to our normal lives ready for service – was a tradition of the Church.

Worth mentioning here are Lumen Gentium 16 and Nostra Aetate (The Church’s Declaration on non-Christian religions). There is a recognition in these two documents that not only Christians, but all women and men when they are honest and true to themselves, seek after the deep mystery that moves the world, that gives meaning and purpose. In this sense, the Church both engages with these fellow pilgrims, while also walking its particular pilgrim paths. The church can learn from other pilgrim paths found all over the world: from the sacred river at Varanasi, or the great Buddhist site of Bodh Gaya, or Jerusalem so dear to Jews, Christians and Muslims – and equally the source of such tensions.

Second, the journey means we have not got there. There are ways that we as a people and as individuals can be re-formed, re-learn, and also be called into question. The Second Vatican Council in particular sought to find the basis for good positive relation between the Church and ‘the world’ – made up as it is by other Christian communities, other religions, and those with no religion. It recognised that while it was privileged to be given the gift of the ‘mystical body’ – it was always in the process of discovering this reality through penance, purification and walking the path. The Council recognised this especially in terms of ecumenism, and subsequent to the Council, there was a recognition of how mission had sometimes been cruel and abusive, not recognising the many true and good elements found outside the church (John Paul’s 2000 apology for past sins of Catholics). Being pilgrims, we have time to step out of the routine, reflect, be formed, listen to the teacher – as the early disciples did on their Emmaus walk.

Another important theme from the Council picked up by Pope Francis was synodality. After the Council the bishops synods became an important focus to help local churches build identity and embrace the gospel. Pope Francis moved this process one step further: in an attempt to listen to the whole people of God, to listen to their worries, concerns, their discernment of God’s signs. It is a risky business and it is not clear where this whole process will go (writing in March 2023), but it is a process that takes seriously our walking and talking together about who we are. We discover this especially when we take time to be with others – especially in a safe environment.

Let me finish with a story related to my walking a ‘nature pilgrimage’ with my wife: England’s South West Coastal footpath. This is 630 miles of mostly glorious, wild, beautiful coastal path – which we are doing in small sections. We’ve had three days of ugly urban backdrops as well. There is something very special about leaving the everyday, which is the most precious arena of our lives. There is something very special about the rhythms of the body enduring a weak ankle, thick rain, and pea soup mist – that is also balanced by the grandeur and awesome beauty of nature. There is something very special and quite challenging about spending so much time together but also discovering the value of companionship and silence in that companionship. All these have enriched us, allowing us to return to the ‘normal’ – even if sometimes, that ankle desperately needs rest.