PILGRIMAGE AS 'COMMUNITAS'

Professor John Eade examines the ground breaking work of anthropologists

Victor and Edith Turner on pilgrimage and their concept of pilgrimage as 'communitas'.

John Eade is Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at Roehampton University,

Visiting Professor at Toronto University and former Executive Director of CRONEM, the Centre for Research on Nationalism, Ethnicity and Multiculturalism.

He is an international expert on the anthropology of pilgrimage and has written widely on the subject.

Until the 1970s the academic study of pilgrimage was largely undertaken by historians who focused on Christian pilgrimage in pre-modern Europe. Since then there has been a veritable explosion of pilgrimage studies which have focussed on contemporary societies around the world and a wide variety of manifestations (religious, spiritual and secular). The intimate relationship between pilgrimage and tourism has led to the emergence of such hybrid terms as pilgrimage tourism and religious tourism which reflect the ways in which pilgrimage has been both supported and shaped by the global expansion of the travel and tourism industry since the Second World War.

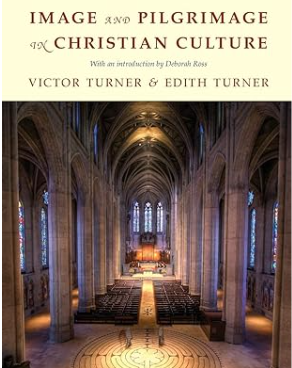

The expansion of pilgrimage studies owes a huge debt to the pioneering study of Christian pilgrimage in the Americas and Europe by Victor and Edith Turner ‒ Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture (1978). Victor Turner was a British anthropologist who undertook research in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) during the 1950s and 1960s. He focused on the role played by ritual in resolving conflict within tribal society and the 1978 book drew on his earlier publications, particularly The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (1969), where communitas refers to freedom from structure. However, this freedom is expressed in three different ways through (a) existential communitas where people relate to one another spontaneously, (b) normative communitas where spontaneity is preserved through ‘a system of ethical precepts and legal rules’ (1978: 252) and (c) ideological communitas where people seek to change the status quo through reform or revolution inspired by utopian ideas. In Image and Pilgrimage the Turners combined this typology with the long established idea of liminality where rites of passage, such as weddings, involved a period of transition where people stood on the threshold (limen in Latin, hence liminal) between two social identities, such as bachelor and husband.

For the Turners, then, contemporary pilgrimage to the shrines they visited such as Knock and Lourdes was characterised by a freedom from social structure celebrated through rituals which emphasise what unites people rather than divides them. As Roman Catholic converts (they joined the Church in 1958) they understandably saw Lourdes, for example, as a place where pilgrims could celebrate their membership of the Universal Church through the particular Marian devotions performed there and the relaxed mingling with others in the shops, cafes, restaurants and bars of the pilgrimage town. This very impressive deployment of old and new concepts (liminality and communitas) provided a model for studying contemporary pilgrimage which has proved highly influential in the expanding field of pilgrimage studies. Pilgrimage was no longer relegated to the past and to a particular area of the world (medieval Christian Europe).

Yet, the model is one sided and this was made very clear by Michael Sallnow, who studied pilgrimage among the Quechua in the High Andes of Peru during the 1970s. His experience of accompanying the Quechua pilgrims to the sacred destinations of a mountain glacier and a cave led him to conclude that Andean regional devotions were characterised by competition and hierarchical division rather than communitas and solidarity. As they walked to the destination groups of pilgrims sought to demonstrate their devotion in competition with one another ‒ they wanted to show how devoted they were through their endurance and performance.

Michael Sallnow’s critique of the Turnerian paradigm made sense to me since I had observed at close quarters the underlying tensions and competition between pilgrims through working as a helper at Lourdes since the late 1960s. So although the religious celebrations, which emphasised the solidarity and unity of the pilgrim Church, were an integral aspect of the Lourdes experience, a lot more was going on. Difference, shaped by the solidarities of nation, region, language, class and gender, in particular, could often make for misunderstanding and tensions. Furthermore, different groups and individuals could discreetly compete in displays of religious devotion and observance of the norms maintained by those managing the shrine. As helpers our job was to assist pilgrims in observing those norms and we were sometimes seen as preventing rather than facilitating the expression of people’s desires. Telling pilgrims that the time for entering the baths was over, for example, could be quite unpleasant, particularly if there was no shared language.

So pilgrimage did not involve a straightforward freedom from structure but a process characterised by both equality and inequality, collaboration and competition, similarity and difference. Given the international character of Lourdes and other popular Catholic destinations such as Rome, Assisi, Lisieux and Santiago de Compostela, it was not surprising that social and cultural differences were prominent. Furthermore, with so many people wanting to express their devotion in many different ways rules and regulations were important but they could cause frustration, friction and sometimes anger and hostility.

The complexity and heterogeneity of pilgrimage defied any straightforward transition from structure to communitas, therefore, and the reasons why people went on pilgrimage were also complex and often ambiguous. This ambiguity and ambivalence was evident when talking to others at Lourdes about the difference between pilgrims and tourists. Despite superficial differences in dress and behaviour, when I talked to ‘tourists’ it was clear that their views about Lourdes were much more complex than many self-identified ‘pilgrims’ assumed. This complexity reflected the ambiguity and ambivalence I noticed among those I worked with as a helper, as well as my own thinking about Lourdes and my involvement there. As a professional anthropologist I am trained to explore the complexities of people’s thoughts and behaviour including my own (!), so this helps get behind facades and simplistic typologies. What people mean when they talk about such identities as ‘pilgrim’, ‘tourist’, ‘Catholic’, ‘religious’ or ‘spiritual’ has to be understood in all its rich diversity ‒ a diversity that often reveals many contradictions and uncertainties.

During the 1990s and beyond academic researchers have explored this complexity and diversity as the study of contemporary pilgrimage moved away from its narrow focus on Christian pilgrimage in Europe and the Americas. At the same time communitas has become a familiar trope used around the world and in a variety of academic disciplines. When historians, for example, draw on social scientific models for their analysis of pilgrimage, they often deploy this trope and assume that this foray into another disciplinary world is sufficient. At the same time, repeated outbreaks of conflict at pilgrimage shrines and violence against those travelling on pilgrimage have shown the diverse ways in which pilgrimage cannot escape social, cultural, political and economic forces shaping contemporary society.

Victor and Edith Turner were well aware of opposites ‒ not only the opposition between communitas and structure but also that between whole and part, homogeneity and heterogeneity, equality and inequality, simplicity and complexity ‒ but saw them as interrelated. However, these opposites are not necessarily connected. The detailed exploration of specific pilgrimages and the complexity of people’s often inconsistent and contradictory meanings and behaviour reveals a more fragmented and fractured picture. Rather than freedom from structure pilgrimage represents in many respects the messy, inconsistent reality of our structured world.

Communitas is informed by the powerful human desire to ‘get away from it all’ and a substantial volume of research has developed which explores this desire by focusing on the journeys pilgrims make to their destinations. This focus has been encouraged by the increasing popularity of walking the expanding range of pilgrimage routes. Walking to shrines has long been practised in India and Japan but in Europe it has been popularised by the ‘camino’ ‒ the historic routes across France and northern Spain to Santiago de Compostela. The popularity of walking historic routes has encouraged the revival of old routes and the invention of new ones in other areas of Europe where the Protestant Reformation during the 16th century led to the destruction of Catholic shrines and the infrastructure of accommodation, monasteries, and pathways enabling pilgrims to travel to and from these destinations.

The concept of communitas has once again been pressed into service by both academics and the promoters of these new routes. Yet, when I joined two one-day walks organised by the British Pilgrimage Trust, it became clear that the understandable and laudable emphasis by the organisers on harmony and unity between the walkers belied the more complex reality revealed by studies of what happens at the destinations. I saw that people brought their different ideas and values of their everyday world to the walk, even if they usually kept these differences to themselves. Walking encouraged this practice since many people walked with friends and only talked briefly to people they did not know.

The only chance I had to I discuss pilgrimage in some detail was during a lunch on the second walk when I sat with some of the group and briefly talked about my interest in pilgrimage. When I mentioned that I had gone to Lourdes many times the discussion petered out amid a palpable coolness in the atmosphere. It became clear later that some of the walkers wondered about the relevance of institutional religion to contemporary pilgrimage. Not surprisingly, people brought the beliefs and values of the structured world with them but kept them quiet in the interest of a temporary harmony. This reminded me of another powerful model developed by the Canadian-born social scientist, Erving Goffman, who distinguished between the front stage and back stage of human interaction. Drawing on theatre he showed the many ways in which the beliefs and values we espouse at the front stage differ from those we express in the back stage. Given the transitory, episodic world of walking most interaction takes place at the front stage ‒ difference and the diverse complexity evident at shrines is kept to the back stage.

Compartmentalisation is another helpful concept for understanding this complexity. It describes the human capacity to resolve contradictions, tensions and conflicts by separating feelings, thoughts and behaviour into compartments. Compartmentalisation is particularly evident at the front stage – we keep the beliefs and values which might conflict with those espoused by others to the back stage of our private world.

Pilgrimage studies has opened up another rich area for exploration. Over the last twenty years rather than focus on human society some researchers have drawn on the turn within the social sciences and humanities towards examining the ways in which human society is shaped by the wider environment. Animals, nature and spirits play a crucial role in our life and this appreciation of other-than-human forces reflects the growing concern about climate change, our responsibility for such change and how a changing environment is affecting our lives. According to this approach we live in an enchanted world where we sensually and emotionally engage with springs, trees, wind, rain, pathways and spirits rather than the disenchanted world envisioned by those, who believe that our world is becoming increasingly secular.

Although pilgrimage studies has moved a long way from Victor and Edith Turners’ pioneering volume, communitas remains a powerful and attractive concept. The belief that we can escape our everyday, structured routines into a liminal world of anti-structure is promoted by media invocations to ‘get away from it all’. Hollywood road movies and tourism invitations to ‘escape’ to some ‘paradise’ where local people and nature are compliant and subservient provide just two examples. Yet this powerful desire for freedom, unmediated unity and harmony coexists with a darker and more complex reality that reflects the tensions, divisions, conflicts and ambiguities of our structured world. Pilgrimage is different from our everyday world but we remain outside the Garden of Eden!