Margery Kempe: a 'woman in motion'

Margery Kempe, who worshipped in Kings Lynn Minster (pictured above), was an extraordinary woman and an indefatigable medieval pilgrim.

Walkers passing through the town of Oroso in Spain on the Camino Inglés will meet one of England’s most famous medieval pilgrims. Far from her home in Kings Lynn, Margery Kempe has been immortalised in stone close to the bridge she would have crossed on her way to St James’s shrine in Santiago de Compostela. But who was Margery Kempe and why is she commemorated so far from her native county of Norfolk?

Margery is one of those colourful personalities who attracts a variety of different responses. To many she is an acclaimed mystic, to others she is an intrepid pilgrim, and to some she is a religious fanatic given to loud, public displays of weeping and wailing. Her overly emotional behaviour has been pathologized as, among other things, postnatal psychosis and Jerusalem syndrome.

These modern perceptions of Margery are not so different from those of her fifteenth-century contemporaries. Although Margery had many supporters, others were unimpressed by her noisy religiosity, suggesting she had drunk too much wine or was possessed by a wicked spirit. A friar alleged she had a heart condition rather than a gift from God, while less generous detractors wished she were “put out to sea in a bottomless boat”.

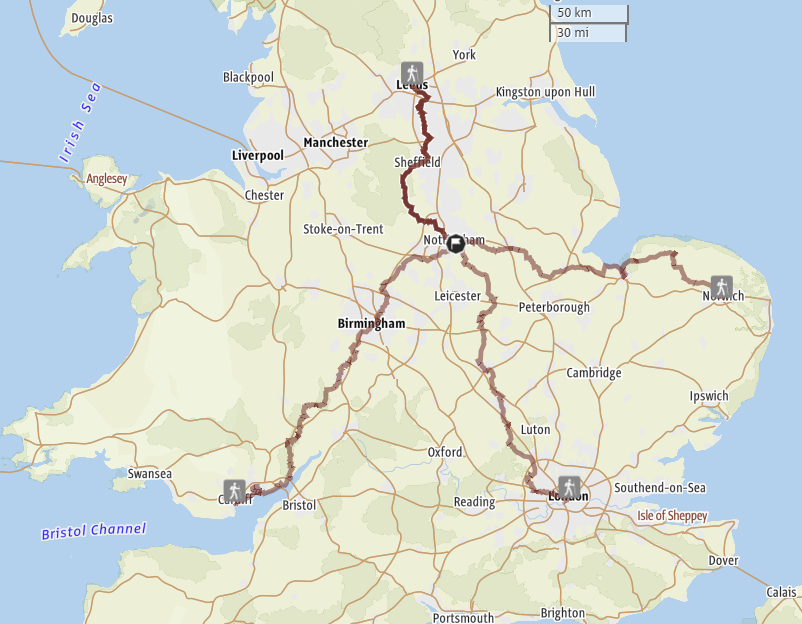

Despite her famed eccentricities, Margery is today perhaps best known as a pilgrim. Born in 1373 and married at the age of twenty, she took up religious travel later in life leaving behind fourteen children and several failed business ventures. She travelled widely across England, visiting many of the country’s foremost pilgrimage destinations including Canterbury, York, and Walsingham. Her overseas journeys took her to the celebrated shrines of Wilsnack and Aachen in Germany, to Rome and Jerusalem and, of course, to Santiago de Compostela where she followed the Camino Inglés and passed through Oroso.

Considering her lack of formal education, one of Margery’s greatest achievements was to author, with the help of scribes, a book narrating her life story. The Book of Margery Kempe – which might be described as a free-thinking, religious autobiography in homely Middle English – is the main medium through which we get to know this extraordinary medieval woman and learn about her numerous pilgrimages. While Margery was not the only female travelling on pilgrimage in the fifteenth century, she is unique in that no other woman of her time recorded her journeys with quite so much passion and in such detail.

As well as telling us much about pilgrimage in the late Middle Ages, Margery’s Book highlights some of the challenges faced by women on long-distance journeys. Margery herself comes across as a tough, determined, and resilient traveller. She took her first pilgrimage in her forties and, at the age of sixty with a painful leg, she made her way across eastern Germany sleeping in barns and valiantly trying to keep up with her younger companions. She was also fearless, instructing the Archbishop of Canterbury to rebuke his household for swearing, and brazenly telling the Archbishop of York – who had apprehended her for questioning – that she “had heard tell” that he was “a wicked man”. However, we also glimpse Margery in her more vulnerable moments: we witness her terror at sea during a life-threatening storm, and her constant worry of sexual assault as a lone female pilgrim.

Margery, of course, is no ordinary pilgrim and her pilgrimages are all the more hazardous because of her unconventional behaviour. On a visit to Canterbury, her exuberant weeping not only annoys the monks and priests; it also embarrasses her long-suffering husband, John, who disowns her for a day. Things get worse when Margery entertains a street crowd with stories from Scripture. How did an illiterate woman have access to these religious texts, people ask? Surely she was either a heretic or possessed by the devil? All alone outside the gates of Canterbury, Margery trembles with fright as people shout, “Take her and burn her!” She is eventually rescued by two men who escort her safely to her lodgings.

The pilgrimage which receives the most attention in Margery’s Book is her journey to the Holy Land. Like other late-medieval pilgrims, Margery spends her time touring the popular Biblical attractions such as the Holy Sepulchre Church in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, the River Jordan, and the Mount of Temptation. Needless to say, her trip is far from trouble free. Her noisy weeping and her habit of constantly talking about God – even at the dinner table – makes her very unpopular with her companions. On the voyage out, her fellow pilgrims try to abandon her and, when that fails, they attempt to shame her by forcing her to wear foolish clothing. Their spiteful bullying continues all the way to Jerusalem: they threaten to turn her maidservant against her, they steal her money, and they confiscate the bedding necessary for her sea passage.

Once in Jerusalem, however, Margery comes into her own. As was the custom, she and her pilgrim companions spend twenty-four hours in the Church of Holy Sepulchre and are shown around by their Franciscan hosts. Margery follows them with her candle, weeping without restraint. When they reach Calvary, Margery collapses, writhing and crying aloud, claiming she could see the Crucifixion and Christ’s body punctured with “more holes than any dovecot”.

The pilgrimage we hear about the least is, ironically, Margery’s journey to Santiago. We know she took ship from Bristol, reached Santiago in seven days, and stayed for two weeks. She must have passed through the town of Oroso as she followed the “English Way” from the port city of La Corũna to Santiago, but the only trace of her today is the modern statue in which she smiles benignly at travellers passing across the town’s medieval bridge.

One reason we hear so little about Margery’s Santiago pilgrimage is because the Book of Margery Kempe is a spiritual memoir rather than a travel account. Margery’s main purpose was to inform her readers about her mystical visions, her special relationship with Christ, and her religious conversations and musings. In this respect, some of her most striking pilgrimages are not geographical but spiritual. Margery had the ability to travel in her mind, and her Book includes several episodes in which she effectively time-travels back to first-century Palestine and interacts with some well-known Gospel characters.

One of the most vivid of Margery’s virtual pilgrimages occurs during an Easter spent at home in Lynn. While in contemplation in her parish church, she is spiritually transported to Jerusalem where she witnesses Christ’s passion. She sees Christ arrested, and then tortured and beaten. After Christ’s burial, Margery accompanies the Virgin Mary home, and there follows a touching scene where the grief-stricken Mary lies on the bed and Margery comforts her by making her a hot drink of spiced wine.

Despite her extensive wanderings, Margery’s life was anchored at home in the Norfolk town of Lynn, now Kings Lynn. It was to Lynn where Margery always returned after her travels, and it is here where she dictated her Book to her two scribes, close to the parish church of St Margaret’s where she experienced her Easter vision.

In many ways, it is more fitting to commemorate Margery in her hometown rather than on a road in Spain, and another statue of Margery now stands in what was once her parish church, Kings Lynn Minster (see images above and below). Entitled, “A Woman in Motion”, the sculpture by Rosemary Goodenough nicely captures two sides of Margery’s personality. Head bowed in prayer, she is static and rooted in her parish church. And yet, at the same time – and dressed in swirling pilgrim attire – she is off and away to her next pilgrimage destination.

Anne E. Bailey

____________

Suggested Reading

The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. and trans. Anthony Bale (Oxford World’s Classics, 2015)

Anthony Bale, Margery Kempe: A Mixed Life (Reaktion Books, 2021)

Anthony E. Goodman, Margery Kempe and her World: Urban Culture and Religious Experience in Later Medieval England (Routledge, 2002)

John Arnold and Katherine Lewis (eds.), A Companion to the Book of Margery Kempe (Boydell & Brewer, 1994)

Laura Kalas and Laura Varnam (eds), Encountering the Book of Margery Kempe (Manchester University Press, 2021)

'A Woman in Motion' sculpture by Rosemary Goodenough in Kings Lynn Minster